LOS ANGELES — When Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy were undergraduates at Stanford University, they made an unconventional observation about what makes a social network valuable.

Thanks to the rise of Facebook, most everyone believed that networks became exponentially more valuable by amassing more users. But Spiegel noticed that in real life, even people with thousands of acquaintances spent most of their time with just a few friends whose value outweighed a large number of looser ties.

So when Spiegel and Murphy created Snapchat in 2011, they inverted the social networking dynamic. Out of their Stanford dorm rooms, they made Snapchat as an app that would send disappearing messages and photos in a way that more closely mimicked the dynamics of a real world conversation. That would increase the appeal of Snapchat as a service that people used with a small number of good friends, they figured.

While online identity previously emphasized everything anyone has ever done, with Snapchat “my identity is who I am right now,” Spiegel said in a 2015 video to describe the app.

Spiegel, 26, Snap’s chief executive, has since built a budding digital empire based on that initial unconventional insight — and has continued upending the tech industry with his different way of seeing the world, often with a touch of ego. Rather than accept the norms of the social networking ecosystem, he has stuck to atypical viewpoints on matters from mobile video to video-recording spectacles. And he has done all of this more than 350 miles away from Silicon Valley, in the sunny climes of Venice, California, where Snapchat is based.

Spiegel’s singular approach will soon be more publicly on display. This week, Snapchat’s parent company, Snap, is expected to reveal its public stock offering paperwork. The filing will show how Snap is doing as a business and whether that justifies a public valuation of $20 billion to $25 billion, which the company has been reported to be seeking. It will also disclose Spiegel’s ownership stake in Snap; the public offering is set to vault Spiegel and Murphy, who is chief technology officer, into the ranks of other tech billionaires.

Along with financial information, Spiegel is expected to include remarks about Snap’s mission that will showcase his zag-while-zigging philosophy.

“If you want to understand Snap, look at Evan Spiegel,” said Todd Chaffee, a partner at IVP, one of Snap’s three largest venture capital investors. “He is the visionary who drives that company.”

Mary Ritti, a spokeswoman for Snap, declined to comment for this story.

Spiegel grew up in Pacific Palisades, a wealthy Los Angeles suburb, and attended Crossroads, a prep school in Santa Monica, California, that counts Jonah Hill, Kate Hudson and Jack Black as alumni.

He lived a privileged life, with expensive cars, exclusive club memberships and fancy vacations, according to records from his parents’ divorce proceedings. His father, John Spiegel, a securities lawyer who helped overhaul the Los Angeles Police Department after the Rodney King beating in 1991, also had his children volunteer and build homes in poor areas of Mexico.

While many techies talk about how the industry is a meritocracy, Spiegel has not shied from his wealthy roots. In public comments, he has said he is “a young, white, educated male who got really, really lucky. And life isn’t fair.”

At Stanford, also his father’s alma mater, Spiegel majored in product design and started a handful of companies with Murphy, a fellow Kappa Sigma fraternity brother. (Their early startups flopped.) There, Spiegel also met some of the men who would become his mentors, including Scott Cook, then the chief executive of Intuit, and Eric Schmidt, the Google chairman, who taught an MBA class that he attended.

Spiegel “really is the next Gates or Zuckerberg,” Schmidt said in an interview, comparing the Snap chief to Microsoft’s co-founder, Bill Gates, and Facebook’s chief, Mark Zuckerberg. “He has superb manners, which he says he got from his mother. He credits his father’s long legal calls, which he overheard, to giving him perspective on business and structure as a very young man.”

When Snapchat started taking off, Spiegel did not wait to graduate from Stanford. He moved the company to the Venice Beach boardwalk, away from what he perceived as Silicon Valley’s too-narrow focus on technology.

His decamping for Southern California put off some in Silicon Valley. The perception of a divide with Silicon Valley was also fostered by Spiegel’s rejection of a $3 billion acquisition offer from Facebook in 2013. Some who met Spiegel during Snapchat’s early days at Stanford describe him as akin to the villain of a 1980s teen movie. He often came across as having a healthy ego, an impression Spiegel sometimes stoked.

When Spiegel met Institutional Venture Partners to discuss possible fundraising, for example, he told IVP’s partner, Dennis Phelps, that he was unwilling to accept the firm’s standard investment terms.

“If you want standard terms, invest in a standard company,” Phelps recalled Spiegel telling him. IVP went on to invest in Snap’s third financing round in 2013.

In Los Angeles, Spiegel has shown interest in the city’s fashion, art and music scene. He met his fiancée, the model Miranda Kerr, at a Louis Vuitton dinner. And he once toyed with the idea of owning a record label with ties to Snapchat, according to a 2015 email between Sony executives that was released by hackers.

“He’s different from most tech people because he knows what’s cool and what’s next,” said Ryan Wilson, an artist in Los Angeles who worked with Spiegel on a piece of art for one of Snapchat’s offices. “He doesn’t like things because a dealer says he should. He just likes what he likes, whether it’s made by a high school friend or a famous artist.”

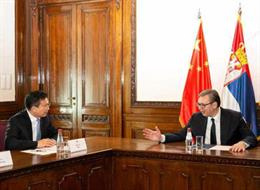

Spiegel has involved himself in some political conversations. In 2015, he met with China’s president, Xi Jinping, as a member of the 21st Century Council at the Berggruen Institute. Its founder, Nicolas Berggruen, said he impressed a group that includes Mohamed El-Erian, the economist, and former president Nicolas Sarkozy of France with his “thoughtful and mature approach to people.” Last fall, Spiegel also attended a private dinner with John O. Brennan, then the director of the CIA. According to multiple attendees, Spiegel listened more than he spoke and had the ear of Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles.

Spiegel’s unconventional streak may be most evident in how he has steered Snap. He has long said that a public offering was what was best for the company and its investors, even as other tech startups chose to stay private as long as possible.

Since Snapchat’s debut, the app and the company have also undergone dozens of changes that were criticized for being too different from other consumer internet companies.

Spiegel rejected the idea of a newsfeed in Snapchat’s app, for example, because he said people prefer stories chronologically. In Facebook’s News Feed, posts are reverse chronological, meaning the newest posts are at the top.

Unlike other social networks, Snapchat also does not use algorithms to push people to see certain content. Snapchat users swipe their screens to navigate and view video vertically, rather than tap on menus or turn their phones to watch videos horizontally.

“From what I can figure out, he thinks differently about the way to monetize and develop a social network,” Schmidt said of Spiegel.

Investors who buy into Snap’s initial public offering will soon be getting a piece of that approach.

Allowing “ourselves to be pulled in another direction” is what makes us human, Spiegel said in a commencement speech at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business in 2015. Quoting John F. Kennedy, he added, “Conformity is the jailer of freedom and the enemy of growth.”

The Toronto Star and thestar.com, each property of Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, One Yonge Street, 4th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5E 1E6. You can unsubscribe at any time. Please contact us or see our privacy policy for more information.

Our editors found this article on this site using Google and regenerated it for our readers.